The Policy Analysis Team at the Western Development Commission (WDC) has compiled a set of Timely Economic Indicators (TEI) for the Western Region (WR) and wider Atlantic Economic Corridor (AEC).

The seventh report in the series has been published today.

In this Insights blog post, I provide a commentary on the report.

Before delving into the TEI indicators it is important to discuss the general economic outlook.

General Economic Outlook

The Irish economy showed resilience and recovery in 2021. Modified Domestic Demand (MDD), likely the best indicator of domestic economic activity, grew 6.2 per cent in 2021 (McQuinn et al., 2021). The national COVID-adjusted unemployment rate averaged 16% during 2021, falling to 7.5% in December, representing a considerable reduction from the 2020 average of almost 20%.

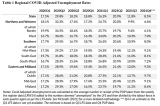

The CSO does not calculate regional COVID-adjusted unemployment rates but I have made estimates which show encouraging signs of regional resilience and the importance of the regional contribution to national economic activity during 2021 (see methodology in McGrath, 2021).

Table 1 shows that Dublin was the NUTS3 region with the highest COVID-adjusted unemployment rate during 2021 with the lowest rates recorded in the Border (Cavan, Monaghan, Sligo, Donegal, Leitrim) and West (Galway, Mayo & Roscommon) regions which together comprise the NUTS2 Northern and Western Region, a close proxy for the Western Region (Clare, Galway, Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon, Sligo and Donegal).

The improvement in COVID-adjusted unemployment in the Northern and Western Region has been driven by sharp employment growth, particularly in the Border region, as well as a sharp decline in both traditional unemployment and PUP recipients in the Border and West regions. Border region employment grew 19% from Q3 2020 – Q3 2021 compared with national growth of 10% over the same period. PUP recipients fell 42% in the Border and West regions over the same period, compared with a national decline of 40% and traditional unemployment fell 41% (27%) in the Border (West) region compared to a national decline of 17%.

The remarkable recovery in the Irish labour market and the extent of economic growth is also evidenced by the national public finances moving onto a more sustainable path. The general government balance, the difference between government spending and revenue, is expected to reach 2.3% which would be within the pre-pandemic EU fiscal rules that were relaxed to aid the fiscal response to the crisis across the EU (McQuinn et al., 2021).

There is less clarity surrounding the financing of local government. In the short term, the central government has mitigated the budgetary impact of the pandemic through the rates waiver scheme, for example, which compensates local authorities for rates income forgone. As we emerge from public health restrictions there are important policy questions surrounding local authority financing. In the Policy Insights section below, I discuss recent research by (Turley and McNea (2021) and their proposals in relation to more sustainable local authority financing.

The economic projections for 2022 are encouraging. MDD is expected to grow 7.1% and national unemployment is expected to fall to 5% (McQuinn et al, 2021). These estimates of economic performance will depend on the trajectory of several risks facing the economy over the next 12 months (McQuinn et al, 2021).

The first risk is the development of the pandemic and related public health restrictions. There are clear and encouraging signs in this regard, given the removal of virtually all public health restrictions at the end of January 2022.

The second risk is inflation following a revision of inflation expectations upwards to 4% for 2022 (McQuinn et al., 2021). Some inflationary pressure is transitory and due to pandemic specific issues, such as supply chains struggling to keep pace with increased demand following eased public health restrictions. These supply chain issues driving up prices have been an international phenomenon (Rees and Rungcharoenkitkul, 2021). However, McQuinn et al. note that given the extent of the recovery in Ireland “the domestic economy is particularly sensitive to these pressures”.

Another risk area is Brexit and the ongoing issues surrounding the Northern Ireland Protocol and the potential triggering of Article 16. Trade disruptions are a particular concern for the Western Region given the comparatively high level of employment exposure in Brexit impacted sectors (see previous Insights blog post).

Labour Market

The combined share of the Western Region’s (AEC) labour force receiving the PUP, wage subsidy or on the live register fell to 21.2% (21.7%) at the end of October down from 33-34% a year ago and 50-51% in May 2020.

However, regional and within region, variation remains. For example, the share of the labour force in those categories combined, within the AEC counties, ranged from 17% in Roscommon (the lowest rate in the country) to 25% in Donegal and Kerry. An encouraging sign is that this is the first TEI report that did not find Kerry to hold the highest rate in the country (Louth 26%). However, four of the seven highest rates in the country are in the AEC (Donegal 25%, Kerry 25%, Clare 22% & Mayo 22%).

The regional and within region variation in the labour market has been documented by Lydon and McGrath (2020) and McGrath (2021) as a key feature of the pandemic. Those studies suggest that the variation is related to, and has in some cases exacerbated, pre-pandemic regional structures of economic activity and employment.

Persons receiving the PUP reached their lowest levels during the first week of December before rising in response to the increased public health restrictions. During the first week of January, 9,883 persons in the Western Region received the PUP (2.5% of the 2016 labour force).

Wage subsidy supports, as a share of the labour force, have generally been lower in the WR & AEC than the national average. At the end of October, 11.1% (11.5%) of the WR (AEC) labour force were supported by the wage subsidy compared with 11.5% nationally. It is encouraging that the WR & AEC wage subsidy supports are close to the national average given these payments are tied to employment.

Consumption

Total new car registrations in the WR & AEC rose 13% in 2021 compared with 2020. Nationally, registrations rose 21%. Compared with pre-pandemic 2019, registrations were 3-4% higher. Nationally, registrations remained 10% below 2019 levels.

During 2021, new goods vehicle registrations grew 41-54% in the WR & AEC, on an annual basis. Nationally, there was a 43% increase. Registrations were 26-29% above 2019 levels in the WR & AEC. Nationally, registrations were 9% above 2019 levels.

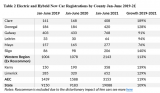

Another key trend that emerged during 2021 was the uptake of electric and hybrid vehicles. Electric and Hybrids combined accounted for 26% of total new cars licenced in 2021 up from 10% in 2019 – part of this 2021 spike is due to huge price inflation in the used car market driven by Brexit and COVID supply shocks making new hybrid/electric cars more attractive. County-level data is currently available for Jan-June 2021. Table 2 shows strong growth in the Western Region and AEC, particularly in Clare and Sligo.

Housing and Construction

The story of the housing market in 2021 was clear, housing demand has held up well and continued to outpace supply thus prices have continued to rise. The supply of available houses for sale rose during 2021 but from an extremely low base. The sales and rental price trends reveal similar patterns to suggest the pandemic has coincided with an initial movement away from larger urban areas, particularly Dublin. Whether this reflects a longer-term trend should become clearer as the remaining restrictions are lifted and new working patterns become established.

Median sales prices, based on the CSO market transaction data, show a rise in sales prices in all AEC counties when comparing Jan-Oct 2021 with 2019. This data is limited as it does not account for size etc. The official source for house price changes is the Residential Property Price Index (RPPI). The RPPI is unavailable at the county level but is available at the NUTS 3 regional level. The RPPI for November shows Dublin prices increased 12.8% in the year to November, while property prices outside Dublin were 15% higher. The Border region saw the largest increase at 24%. Similar trends are recorded for 2021 in the Daft.ie Q4 House Price Report where, year-on-year, list prices have risen faster outside of Dublin and the other cities, a saliant example is Galway city rising 1.6% compared with a 16% rise in Galway county. The largest increases have been in the cheapest markets, for example, Leitrim saw an annual rise of 19% (Lyons, 2021).

Lyons notes that the annual national change in list prices for Q4 2021 was 7.7% the same as in 2020 and close to the average of 7.8% from 2015-2018. Lyons notes that 2015-2018 was the period just after the Central Bank imposed lending restrictions to counteract large property price increases but before increased supply had its effect (there was slow or negative growth prior to the pandemic). Lyons provides an excellent discussion of the property boom just prior to the introduction of the Central Bank lending rules “It is perhaps largely forgotten now but the country very nearly went down the path of another housing bubble in the mid-2010s…. In the third quarter of 2014, the Daft Report showed that prices in Dublin had risen by just under 25% in one year….,the Central Bank realised it had to take action to control conditions in the credit market ‐ in particular, the amount of leverage households were able to take on, the key problem in the 2001-2007 bubble ‐ and thereby rein in expectations of future price increases. Lyons notes the sales market today is more about fundamentals and characterised by “the underlying dynamic of weak supply given strong demand”.

Similar trends are found in the rental sector. Rents rose annually in all AEC counties during Q3 2021. Increases ranged from 6.1% in Limerick to 21.5% in Leitrim. Four of the five largest annual increases in the country were in the Western Region; Leitrim (21.5%), Clare (17.5.%), Donegal (17.2%) and Sligo (15.4%). The national annual increase in rents was 8.3%, driven downwards by Dublin (6.0%).

Western Region & AEC dwelling completions, commencement notices and planning permissions granted were all above pre-pandemic (2019) levels during YTD 2021. A sharp fall in Dublin (-24%) drove national completions below 2019 levels. Q4 2020 recorded the highest level of completions in the CSO dataset (available back to 2011). Consequently, a strong Q4 is still needed to match the high 2020 level recorded in the WR & AEC. For example, the WR needed 844 completions during Q4 2021 to match the 2020 total. 1,001 dwellings were completed during the peak of Q4 2020, equivalent to the entire year of 2013. 800 dwellings were completed during Q4 2019 and 605 during Q4 2018. Total dwelling completions during 2021 are likely to be close to the 2020 level of 20,532 and thus lower than the projected new housing demand of 31,000 in 2021 as estimated by Bergin & García Rodríguez (2020). Lyons (2021) estimates a higher housing demand of closer to 50,000.

Policy Insights

The relaxation of public health restrictions clearly raises the question of the elimination of supports for businesses and workers. Policymakers must be wary of potential cliff-edge impacts such as those outlined in Keane et al., (2021). For example, the withdrawal of the PUP may inhibit employees from returning to work as they may face reduced hours in the short term. The authors argue that providing support to those in part-time or low-paid employment would offer a financial incentive to work while maintaining living standards and that a simple option would be to permit PUP recipients to retain some of their payment as they return to work. The government has recently announced the end of the PUP for new claimants from January 22nd and that from March 8th those still in receipt of the PUP will move to a weekly rate of €208. PUP recipients will then start transitioning to standard jobseeker terms, and if eligible, will move onto a jobseeker payment from April 5th. The Government also announced that the Wage Subsidy Scheme would stop at the end of April for sectors that were not impacted by the last public health restrictions, and the rate of subsidy would reduce in the meantime. For hospitality and live entertainment, the higher rate of the wage subsidy will apply until the end of February before the scheme stops at the end of May. In relation to the wage subsidy, Keane et al. note that the government has followed OECD suggestions to remain flexible and to align subsidy rates with the PUP. In terms of transitionary options, the OECD suggest a slow withdrawal coupled with job search assistance and training opportunities. Keane et al. suggest that generous short term work schemes may be a viable and flexible alternative to wage subsidization after the wage subsidy is fully withdrawn.

Another policy question as we exit public health restrictions surrounds the issue of local government financing in the face of the removal of the rates waiver scheme (the targeted scheme is planned to run until the end of March) and the trends of remote working, online retail, and relocation from larger urban centres. Turley and McNea (2021) propose a broadening of the local authority tax base, through the revenue sharing of motor taxation with central government (from the mid-2010s all motor taxation revenue goes to central government). Turley and McNea argue that this model, based on the principles of local public finance theory, would broaden the local authority tax base while that at the same time permitting a reduction in commercial rates. The authors argue for the extra revenue to be used to reduce commercial rates but that ultimately the usage of the additional revenue would be a matter for each local authority. A reduction in commercial rates, whether on a general or more targeted basis, is preferred by the authors as a means to boost local economic growth in the aftermath of the pandemic. A reduction in commercial rates may also form part of a policy response to aid the high rates of commercial vacancy in the Western Region as recently detailed in a number of reports (EY-DKM, 2022; NWRA; 2022). For illustrative purposes, the authors take the financial year 2019, and motor tax receipts of €964m and take a 25/75 split, with 25% of revenue going to local government on a derivation basis (shared in proportion to the revenue that each local authority collects). Under these assumptions, this results in a 16% reduction in commercial rates income needed for local authorities to balance their adopted budgets. The reduction in the rates income required translates into larger potential reductions in the Annual Rate on Valuation (ARV), more rural councils have a lower share of total revenue from rates and thus the average ARV reduction could be as large as 30%. The authors note that it “is important to restate that these ARV reductions do not mean cuts in local public services or any softening of subnational fiscal discipline. The revenue-sharing arrangement whereby local government is assigned 25% of motor tax revenues affords local authorities the opportunity to maintain the level of public service provision and balance their annual revenue budgets, but all at a lower ARV, as a smaller amount of commercial rates needs to be levied.”

In the medium to longer term, some key policy areas include the delivery of balanced regional development and the related delivery of housing.

The WDC has made recent submissions to the Government across several areas that ultimately provide the framework for regional development policy. Over the medium-term, regional policy is set out in the Department of Rural and Community Development (DRCD) publication “Our Rural Future: Rural Development Policy 2021-2025” with a vision for a “thriving rural Ireland which is integral to our national economic, social, cultural and environmental wellbeing and development…. built on the interdependence of urban and rural areas” (DRCD, 2021). The longer-term vision for regional development policy is contained in Project Ireland 2040 which is comprised of The National Planning Framework (NPF) and the National Development Plan (NDP) with an overall vision of more balanced regional development. These submissions, on the review of the National Development Plan (NDP), the related establishment of the National Investment Framework for Transport and the development of a National Smart Specialisation Strategy, identify key challenges and highlight the ongoing work of the WDC to address these challenges.

To maximise future opportunities and support effective regional development, policy must focus on the reduction of regional infrastructure deficits and broader policies to support innovation and the 3 E’s (Education, Employment & Enterprise). In the face of regional diversity, one-size-fits-all policies that fail to account for regional strengths and weaknesses will not succeed. Building on regional comparative advantage can promote long-term economic development while also contributing to national economic growth. This requires integrated strategies for regional development policy across sectors based on governance arrangements that consider regional needs. The WDC has, in its submission to the National Smart Specialisation process, identified three areas of existing and emerging regional strength; Life Sciences (which includes MedTech), Artificial Intelligence, Data and Analytics (particularly in the area of sensors and mobility) and the Creative Economy. Previous WDC research has also highlighted the region’s comparative advantage in terms of natural capital assets and the associated quality of life. For example, natural capital underpins the region’s scenic beauty which may attract and retain workers in the “new normal” of remote work. The WDC has been a leader in remote work research and also leads the national Connected Hubs Network. The transition towards a low-carbon economy will increase the value placed on natural assets, and consequently their role and importance to the national economy (WDC, 2012). The Western Region, for example, holds a higher reliance on economic sectors such as agriculture, forestry, tourism, marine fisheries, and aquaculture that are reliant on the effective conservation and management of natural capital (WDC, 2012; McHenry 2020a). Conservation and management of natural resources is a challenge that is closely linked to several others e.g., economic resilience, sustainable production, clean energy, sustainable agriculture. The WDC has emphasised the importance of natural capital, green infrastructure and high quality, reliable and sustainable water service for regional development (McHenry, 2020b).

To address housing shortages and to match the vision of the population growth targeted under the National Planning Framework it is clear that housing supply will need to increase across the country over the coming decades. Lyons (2016) provides a detailed outline of the issues and policy options to address key issues in the Irish housing market. Several key issues raised by Lyons are being targeted in the Government’s “Housing for All” strategy such as commitments to tackle the costs of construction, building the institutional capacity through a streamlined planning process, and perhaps most notably the switch from a vacant site levy to a zoned land value tax announced in Budget 2022. The devil will be in the detail and the implementation of these policies but there is a clear government target of 33,000 new houses per year from 2021-30 and a commitment to support local authority housing delivery. The establishment of a Housing Commission was an action under Housing for All and the group has its first meeting in January 2022 with a series of reports due to be published by the end of July 2023.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of the WDC

Dr Luke McGrath

Economist

Policy Analysis Team