Last week was Bioeconomy Ireland Week.

As part of Bioeconomy Ireland Week, Teagasc, in collaboration with others presented an interesting series of maps on Ireland’s bioeconomy. You can find the maps here.

In this Insights Blog, I run through some aspects of the bioeconomy in the Western Region.

The bioeconomy consists of the economic sectors that use renewable biological resources – such as crops, forests, fish, animals and micro-organisms – to produce food, materials and energy.

Table 1 shows the relevant direct sectors by NACE codes as defined by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC).

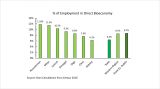

Employment in the Western Region’s Bioeconomy

The bioeconomy is an important employer in Ireland, the national average share of employment was 6.4% and 8.5% within the Western Region (Census, 2016).

There are important regional differences as Dublin (1.4%) skews the national average. Excluding Dublin, the national average was 8.7%.

There is some variation within the Western Region with the largest shares found in Roscommon (11.8%), Mayo (11.5%) and Leitrim (10.3%), well above the Western Region and national averages.

These employment figures understate the importance of the bioeconomy for several reasons, as pointed out by Dr. Jesko Zimmerman (Teagasc).

Firstly, they include only direct employment in what is considered the direct bioeconomy. Employment in partial or hybrid sectors within the bioeconomy is not captured due to data constraints.

Secondly, indirect employment in other sectors, particularly those relating to tourism may be large given the benefit to those sectors of attractive landscapes, for example.

Finally, the bioeconomy is part of our often hidden Natural Capital as the bioeconomy is more than the production of the traditional goods and services that get recorded in the national accounts.

Natural Capital

Natural capital is an economic metaphor for nature and consists of the stocks of renewable and non-renewable natural resources that combine to yield flows of ecosystem services.

Many of the important ecosystem services provided by natural capital are not available for sale in markets thus are missing from our conventional national accounting framework and our conventional measures of economic progress.

Natural capital accounting seeks to highlight these important hidden stocks and flows and is an important objective of the European Union.[1] For an overview of natural capital accounting in Ireland see Farrell et al. (2019) and McGrath et al. (2020).

You can also keep up to date with natural capital developments by following the Irish Forum on Natural Capital and the EPA-funded INCASE (Irish Natural Capital Accounting for Sustainable Environments) project.

Many of the important ecosystem services provided by natural capital are not available for sale in markets thus are missing from our conventional national accounting framework and our conventional measures of economic progress.

Natural Capital accounting and the bioeconomy.

One approach to natural capital accounting is to try and map the extent and condition of nature’s stocks to account for the ecosystem services that flow from these stocks for human benefits.

One example of this approach is the the High Nature Value (HNV) farmland map developed by Teagasc.

HNV farmland is typically characterised by low-intensity farming associated with high biodiversity and species of conservation concern.

The HNV map provides information on the likely occurrence and distribution of HNV farmland by incorporating five indicators of natural capital extent, condition and use.

The map shows a comparatively higher likelihood of HNV farmland occurring in the Western Region.

The map...suggests the Western Region may be comparatively rich in terms of both High Nature Value farmland and cultural services.

The stocks of the HNV landscape include natural capital assets such as native woodlands, hedgerows, wetlands, bogs and streams.

These stocks provide flows of ecosystem services such as provisioning services (e.g. food and timber), regulating services (e.g. carbon sequestration and biodiversity) and cultural services (e.g. amenity and recreation) provided by these stocks.

Lisa Coleman and Dr. Catherine Farrell (INCASE) and Dr Stuart Green & Dr Jesko Zimmermann (Teagasc) looked at the interaction between cultural services and HNV farmland by overlaying the Teagasc HNV map with indicators of cultural services (national parks, pilgrimage trails and national walking trails, and the Wild Atlantic Way).

The map suggests a positive correlation between cultural services and the likelihood of HNV farmland and suggests the Western Region may be comparatively rich in terms of both HNV farmland and cultural services.

The authors argued that “cultural services, as well as regulating services are often unrecognised and unrewarded services, that present further opportunities upon which to build the bioeconomy”.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of the WDC

Luke McGrath

Economist

Policy Analysis Team

Footnotes

[1] Regulation (EU) 691/2011 (as amended by Regulation (EU) No 538/2014).