The Western Development Commission (WDC) has published the latest in its ‘Regional Sectoral Profiles’ series which analyses the most recent employment and enterprise data for the Western Region on specific economic sectors and identifies key policy issues.[1]

This report examines the Construction sector which includes the construction of buildings, electrical and plumbing installation, carpentry, painting, civil engineering (infrastructure projects), demolition etc. It does not however include professional services related to the sector (e.g. architecture, real estate).[2]

Two publications are available:

- WDC Insights: The Construction Sector in the Western Region (2-page summary, PDF 0.2MB)

- The Construction Sector in the Western Region: Regional Sectoral Profile (36-page report, PDF 1.9MB)

Employment in Construction

According to Census 2016, 18,166 people worked in Construction in the Western Region. The past two decades have witnessed dramatic jobs volatility in this sector. The number working in Construction in the Western Region increased by 163.6% (from 16,674 to 43,956) in the decade from 1996 to 2006, followed by a 58.7% decline over the next 10 years (2006-2016).

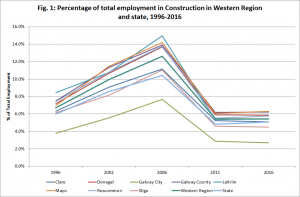

These dramatic changes are clear from Construction’s share of total employment (Fig. 1). In the Western Region, Construction accounted for 6.7% of total jobs in 1996 and by 2006 its share had almost doubled to 12.6%. It sector was consistently more important in the region than nationally.

In the Western Region, the crash led to Construction’s share of employment more than halving to 5.4% by 2011; remaining unchanged in 2016. Nationally, the share also declined sharply to 4.8% in 2011 but its role grew somewhat in 2016 (5.1%) indicating that recovery in Construction in the region lagged that occurring elsewhere.

In 2006, Construction accounted for 15% of total employment for residents of county Leitrim, the highest share in the region, with the largely rural counties of Mayo, Galway County, Roscommon and Donegal also having extremely high reliance on Construction jobs at this time. By 2011, Construction’s share had fallen substantially in all counties. Despite this, all western counties except Galway City and Sligo were still above the national average in 2011.

Between 2011 and 2016 there was 7.8% jobs growth in Construction in the Western Region, less than half that occurring nationally (16.6%), again indicating how recovery in the building sector in the region lagged that elsewhere. Within the region Roscommon (11.1%), Galway County (9.5%) and Donegal (9.3%) had the strongest growth, though all still well below the national average. In contrast to the general trend, Sligo actually saw a decline in the number of residents working in Construction between 2011 and 2016

Employment in Construction in western towns

When considering towns, commuting can be particularly important and it must be remembered that this data refers to residents of the towns, although some may travel to work elsewhere.

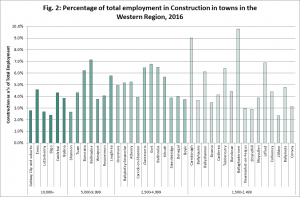

Ballaghaderreen (9.8%, 57 people) in Co Roscommon has the highest share of residents working in the sector in the region (Fig. 2) and is second highest among Ireland’s 200 towns and cities (1,500+ population). Within the region, Carndonagh (9%, 72 people), Ballinasloe (7.1%, 162 people) and Lifford (6.9%, 32 people) have the next highest shares working in the sector. Small and medium-sized rural towns tend to rely most on Construction.

Six towns in the Western Region are among the bottom ten nationally in terms of the share working in Construction, including the large centres of Galway City, Letterkenny and Sligo. Greater economic diversity and more alternative job options reduces reliance on Construction.

Self-employment in Construction

Of the 18,166 people working in Construction in the Western Region in 2016, 39.7% (7,206 people) were self-employed (employer or own account worker). This is the second highest[3] rate of self-employment across all economic sectors due to the nature of Construction sector with many people working in construction trades e.g. electricians, plumbers, being self-employed.

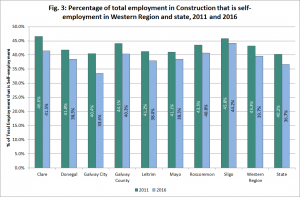

Self-employment is more common in the Western Region (39.7%) than nationally (36.7%) (Fig. 3) with Construction in the region characterised by a higher share of sole traders or micro-enterprises.

The number of self-employed people working in Construction in the region fell by -1.1% between 2011 and 2016. In contrast, nationally, there was strong growth in Construction self-employment (6.2%). In both areas however the share of total employment that was self-employment declined between 2011 and 2016 (Fig. 3), because employee numbers out-performed self-employment numbers, reducing self-employment’s share of the total.

At 44.2%, Sligo has the highest share of Construction self-employment in the region and had the smallest decline in its share 2011-2016. Clare and Roscommon also have 40+% self-employment with Galway City (33.6%) having the lowest share, the only area in the region below the national average. This is influenced by the presence of some large Construction firms in the city.

Construction Enterprises and Persons Engaged

In 2017 there were 11,806 Construction enterprises registered in the Western Region with 23,059 persons engaged.[4] Construction accounted for 20.4% of total enterprises[5] in the region compared with 16.9% in the state (Fig. 4) and was the largest sector in terms of enterprise numbers. As Construction is characterised by many small scale operations however, it only accounted for 9% of all persons engaged in enterprises in the region (6.7% in state) and was the fifth largest sector.

The rural counties of Roscommon and Mayo is where Construction accounts for its highest share of total enterprises, followed by Donegal and Leitrim where Construction also accounts for over 1 in 5 of all enterprises. This reflects lower business diversity leading to greater reliance on Construction. Sligo and Clare, which had low shares of employment in the sector (see Fig. 1), also have the lowest shares of their enterprises in Construction.

In terms of all persons engaged in enterprises, over 11% were working in Construction in Leitrim, Roscommon and Mayo. This reinforces the significant role of the Construction sector in both the enterprise and employment profile of these largely rural counties. Again Sligo has the lowest share in the region (6.7%).

Key Policy Issues

Plays a larger role in the Western Region’s economy, especially in more rural areas: Despite significant decline during the recession and slower recovery than elsewhere, Construction continues to employ a greater share of the workforce and account for a higher share of enterprises in the Western Region. It is particularly significant for the region’s more rural counties and for small and medium-sized rural towns, in terms of jobs, income and enterprises. The experience of the last recession highlights the importance of promoting diversity in the rural and regional economy and, while Construction must play a key role, a return to over-reliance on the building industry poses a risk.

Smaller scale operations and high self-employment: Construction enterprises in the Western Region tend to be smaller and the sector is characterised by high self-employment. The quality of some Construction self-employment, and its ability to sustain a person’s livelihood, are issues to be considered as the sector grows. Supports for Construction sole traders and micro-enterprises such as business skills and financial training, as well as information on emerging trends and opportunities must be a focus for policy.

Important employment role among men including young and lower skilled workers: At the height of the Celtic Tiger 22% of working men in the Western Region worked in Construction and the impact of the recession on Construction greatly increased male unemployment and out-migration.[6] Construction continues to play an important role and in 2016 employed 1 in 10 working men in several of the region’s more rural counties. It also helps to sustain the viability of part-time farms. In total, 94.2% of the total Construction workforce in the Western Region are men.

While Construction includes many highly skilled and well-paid occupations, it is also an important source of jobs for younger and lower skilled workers. It is important that current growth in the sector includes opportunities for people of differing skill and experience levels, while not acting as a disincentive to the pursuit of further or higher education.

Opportunities of a low carbon economy: Adaptation to a low carbon economy, specifically improved energy efficiency and renewable energy, presents a growing opportunity for this sector. Government targets[7] of 500,000 building retrofits and installation of 600,000 heat pumps by 2030 present particular opportunities in the region and its rural areas.

For more detailed analysis, download The Construction Sector in the Western Region: Regional Sectoral Profile and WDC Insights: The Construction Sector in the Western Region here

Pauline White

[1] Previous Regional Sectoral Profiles are available here https://www.wdc.ie/publications/reports-and-papers/

[2] See WDC (2019), Professional Services in the Western Region: Regional Sectoral Profile

[3] The highest is Agriculture, Forestry & Fishing at 76.5%.

[4] Data is from CSO, Business Demography 2017

Each enterprise and all persons engaged in that enterprise are assigned to the county where its head office is registered with Revenue.

[5] Total enterprises includes all ‘business economy’ enterprises (NACE Rev 2 B to N(-642)) plus the sectors of Health & Social Work, Education, Arts, Entertainment & Recreation and Other Services.

[6] WDC (2009), Work in the West: The Western Region’s Employment & Unemployment Challenge

[7] Government of Ireland (2019), Climate Action Plan 2019: To Tackle Climate Breakdown