//

The CSO released the latest data on Income and Living Conditions (Survey on Income and Living Conditions SILC) last week, see here. The headline figures indicate a continued rise in incomes between 2017 and 2018 which in turn was higher than the figures five years earlier, in 2012 (see earlier post on this here). This is in line with other national economic indicators such as continuing economic growth, employment growth and decreasing unemployment. To what extent is a rise in incomes reflected in a decline in poverty rates and how is this distributed at a spatial level within Ireland? This post highlights some recent data and asks does a rising tide lift all boats?

Poverty Rates

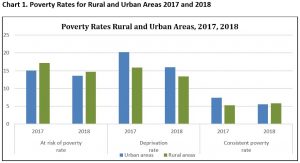

The CSO produce data on three different poverty measures and here we will examine the different rates as they apply to rural and urban areas.[1]

At Risk of Poverty rate[2]

The at risk of poverty rate nationally decreased from 15.7% in 2017 to 14.0% in 2018.The at risk of poverty rate in rural areas in 2018 is 14.7% compared to 13.6% in urban areas. In both rural and urban areas, the trend is downward – in rural areas (down from 17.2% in 2017), and in urban areas 13.6% (down from 15.1% in 2017). This is illustrated in Chart 1 below.

Deprivation Rate

The CSO also measure the deprivation rate, which is a broader measure than poverty and is defined as follows: Households that are excluded and marginalised from consuming goods and services which are considered the norm for other people in society, due to an inability to afford them, are considered to be deprived. The set of eleven basic deprivation indicators are detailed below[3]. Individuals who experience two or more of the eleven listed items are considered to be experiencing enforced deprivation.

Nationally, the deprivation rate has decreased over the last few years. In 2016 it was 21% and it has since decreased from 18.8% in 2017 to 15.1% in 2018. At a spatial level it appears that there is a higher rate of deprivation in urban areas than in rural, in 2018 the urban deprivation rate was 16.0% while in rural areas it was 13.4%. Both of these rates have also shown a decrease from one year earlier, in 2017 the rates were 20.2% and 15.9%. This is also shown in Chart 1 below.

Consistent Poverty

Finally, the other commonly used measure of poverty, is the consistent poverty rate. An individual is defined as being in ‘consistent poverty’ if they are

- Identified as being at risk of poverty and

- Living in a household deprived of two or more of the eleven basic deprivation items discussed above

Nationally the rate went from 8.2% in 2016 to 6.7% in 2017 to 5.6% in 2018. In urban areas the consistent poverty rate declined from 7.4% in 2017 to 5.5% in 2018. In contrast the consistent poverty rate in rural areas increased slightly; from 5.3% in 2017 to 5.8% in 2018.

Regional Difference

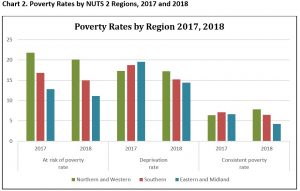

The CSO also publish produce data at NUTS 2 regional level for the different poverty measures.

At Risk of Poverty rate

The regional data indicates that the at risk of poverty rate is higher in the more rural regions (Northern and Western) with 20.1% or a fifth of the population there at risk of poverty in 2018. There was a slight decline on a year earlier (21.8%). This consistent poverty rate in the Southern region is considerably lower 15%, down from 16.8% a year earlier. The Eastern and Midland region has the lowest rate 11.1%, down from 12.8% in 2017.

Deprivation Rate

The deprivation rates are more similar across regions (compared to the at risk of poverty rate), as chart 2 shows, though both the Southern and Eastern and Midland regions recorded more significant declines than that experienced by the Northern and Western Region, so in 2018 the Northern Region has the highest deprivation rate (17.2%), compared to the Southern region (15.2%) and the Eastern and Midland region (14.4%).

Consistent Poverty

A similar pattern is evident when examining the consistent poverty rates by region. In 2017 the Northern and Western Region had the lowest rate (6.4%) but a year later the region reported the highest rate – up to 7.8%. This contrasts with the performance and trends in the other regions both of which recorded declines in consistent poverty levels. The Southern region rate declined from 7.1% in 2017 to 6.5% in 2018. The Eastern and Midland region rate declined from 6.6% to 4.2% in 2018.

Overall the CSO recent data show that rural areas have a higher at risk of poverty rate, compared to their urban cousins, but have lower deprivation rates while the consistent poverty rate is most recently showing an upward trend in rural areas and the Northern and Western region and is higher than urban areas and the Eastern and Southern regions.

Measuring Deprivation: Access to Services?

In a previous blogpost in early 2019, see here, I argued that any measurement of deprivation and poverty is more complicated and other considerations such as access to services need to be taken into account.

Access to services

It is often said that rural poverty and deprivation is more hidden or less visible than that in urban areas and one aspect of this is access to services. The CSO SILC definition of deprivation is based on enforced deprivation where there is an inability to afford goods and services. But what of the inability to access goods and services because they are not available in the locality. The case of broadband is a good example. Most people who cannot access good quality broadband see it as a deprivation. It impacts on a person’s ability to access goods and services on-line and often impacts on their ability to generate their incomes, for small businesses and the self-employed.

What about access to other services? Can limited or no access be considered an indicator or measure of deprivation? The CSO have just published data which provides insights into access to a wide range of services, including transport, health and other services see here. There is extensive data and mapping resources which the WDC will revisit but a snapshot illustrates some interesting differences:

- The average distance to most everyday services was at least three times longer for rural dwellings compared with urban dwellings. For a supermarket/convenience store, pharmacy and a GP, the average distance for rural residents was about seven times longer.

- Examining differences by county, residents in Galway County, Donegal, Mayo, Leitrim and Roscommon had higher average distances to most everyday services when compared against other counties.

- The average distance to 24-hour Garda stations ranged between 1.5km in Dublin City to 19.3km in Donegal, while the average distance to a GP was 3.1km, but was more than 5km in Roscommon, Galway County and Cork County.

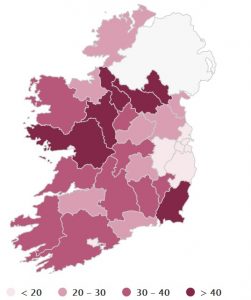

- Half of the people living in Roscommon had to travel 5km or more to visit a GP, followed by Monaghan (48%), Leitrim (43%) and Galway County (43%) as illustrated in the Map below. The darker the colour the higher the percentage of the population living 5km or more from a general practitioner.

Map 1 Percentage of Population 5km or more from a GP location by county

The CSO also provide a useful data dashboard to illustrate in a visual way access to services, see here.

Also this November Trinity published data on data on health and Health services, The Trinity National Deprivation Index 2016 see here . This research examines health and health services at a detailed spatial level (Electoral Division) and highlights regional inequalities.

Conclusions

These different data sources provide really useful insights into the geographic distribution of poverty, deprivation and access to services. Overall, the CSO SILC data indicate that along with rising incomes nationally there is evidence of a decline in poverty rates. However, the exception to this is evidence of rising consistent poverty rates in rural areas and in the Northern and Western region.

After a period of sustained economic growth and rising incomes, it is clear that not all boats are being raised in the rising tide. These data provide a wealth of information highlighting regional and spatial difference and an evidence base for effective policy change. This is a tool to inform Government policy to focus on eradicating poverty and in doing so being cognizant of the spatial patterns of poverty. Various policies ranging from consideration of a new Rural Strategy in the short term to Project Ireland 2040 over the medium to long term are some of the policy frameworks which need to respond to these findings.

Deirdre Frost

[1] Urban or Rural are defined as follows: Urban – population density greater than 1,000. Rural is Population density <199 – 999 and Rural areas in counties.

[2] This is the share of persons with an equivalised income below 60% of the national median income.

[3] Two pairs of strong shoes, A warm waterproof overcoat, Buy new (not second-hand) clothes.

Eat meal with meat, chicken, fish (or vegetarian equivalent) every second day, Have a roast joint or its equivalent once a week. Had to go without heating during the last year through lack of money, Keep the home adequately warm. Buy presents for family or friends at least once a year. Replace any worn out furniture. Have family or friends for a drink or meal once a month, Have a morning, afternoon or evening out in the last fortnight for entertainment.