Recently I attended a very interesting seminar on ‘Migrant Integration: policy and place’ organised by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and the European Migration Network (EMN).

At the seminar two new pieces of research were presented and discussed: ‘Diverse neighbourhoods: an analysis of the residential distribution of immigrants in Ireland’ and ‘Policy and practice targeting the labour market integration of non-EU nationals in Ireland’.

Given the Western Development Commission’s (WDC) regional development remit, the spatial analysis of the residential distribution of immigrants in Ireland was of particular interest. The ‘Diverse Neighbourhoods’ report[1] points out that previous research has highlighted both positive and negative reasons for the residential clustering of migrants. Proximity to migrant networks can provide support and information (as the Irish of the Kilburn Road know only too well). However, high levels of residential segregation may be a signal of poor integration and disadvantage, especially if the areas in which migrants are clustered are themselves deprived.

The purpose of this analysis was to investigate the residential pattern of Ireland’s migrant population, to identify the extent of residential segregation and the characteristics of areas where migrants are concentrated.

Distribution of Migrant Groups in Ireland

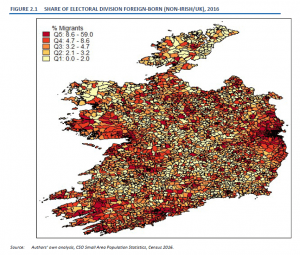

The analysis used the results of Census 2016 for 3,409 Electoral Divisions (ED) in Ireland. Individuals were assigned according to their country of birth (to take account of foreign born naturalised Irish citizens) and UK-born migrants were excluded because they have a different experience and there are complexities for Northern Irish citizens.

Four broad groups were analysed (the size of each group as a proportion of the national population in 2016 is in brackets):

- Total migrant population – excluding UK-born (11.4%)

- EU migrants – excluding UK-born (6.3%)

- Migrants born outside of the EU (5.1%)

- People with poor self-rated English-language proficiency (1.8%).

Total, EU and non-EU Migrants

The total migrant (non-Irish/UK born) population is highly concentrated in urban areas in Dublin city and its commuter belt, as well as around Cork, Limerick and Galway (see Figure 2.1). In fact half of all foreign-born migrants live in the three cities of Dublin, Cork and Limerick. The top 10 EDs in terms of the percentage of their total population who are foreign born were all in Dublin, Limerick, Cork or Waterford cities. Half of the total foreign-born population live in just 159 EDs (out of 3,409 total EDs).

The patterns for both migrants born in the EU and migrants born outside of the EU are relatively similar to the total. For EU migrants, there are high concentrations around Dublin, Cork and Limerick with low concentrations in North Connacht and Donegal. For non-EU migrants the pattern is very similar, though with even greater concentration in Dublin. For both, most of the top 10 EDs are to be found in Dublin, Cork or Limerick.

People with Poor English Language Proficiency

The fourth group examined are people who reported in the Census that they speak English ‘not well’ or ‘not at all’. This group was examined as they may have particular integration difficulties. Nationally there were about 86,000 people in this group in 2016.

It was found that the residential pattern for those with poor English language proficiency differs from the other groups (see Figure 2.4). While there is also significant concentration in the larger cities, this group are less centralised and there are also strong concentrations in small towns.

The ED of Monaghan town has the highest share with poor English language proficiency at 15.3% with is linked to the mushroom industry. Ballyhaunis in Co Mayo has the fifth highest share (11.1%) connected to both the meat processing sector and a Direct Provision Centre. Another town in the Western Region, Roscommon Urban ED has the eight highest share (10.7%). Other smaller towns with high shares include New Ross in Co Wexford, Ballyjamesduff in Co Cavan and Navan in Co Meath.

It seems that migrants with poor English language proficiency are less centralised in the larger cities and are more likely to be located in smaller towns (often linked to specific sector or legacy), they are also more clustered in fewer locations with half located in just 135 EDs. This pattern has implications for service provision.

Integrated Communities

The report goes on to assess the level of segregation of migrant communities. It found that the level of segregation in Irish cities is near or below the international average and there was no discernible trend of increasing residential segregation between 2011 and 2016 with some groups becoming less segregated over this time.

The report also profiled the characteristics of areas which have a high share of migrant residents. It was found that immigrants in Ireland tend to be concentrated in more affluent areas (based on the Pobal Deprivation Index) and also in areas with an above average share with a third level education. The other key characteristic was that migrants tended to be concentrated in areas where private rental housing was plentiful.

One area of concern however are those with poor English language proficiency. This group is more likely to reside in areas with average levels of affluence/deprivation and low third level education attainment. For those living within the three largest cities, they are also concentrated in areas with higher unemployment rates.

Policy Implications

The results have implications for many policy areas including integration, housing and regional development. The National Planning Framework contains targets to rebalance growth towards the ‘second tier’ cities and regions. Reducing the level of concentration of the migrant population in Dublin, through the provision of job and housing opportunities, would contribute to achieving NPF targets. Reliance on the private rental market among migrants means that the provision of such accommodation in other locations is important, as well as employment policies which stimulate job opportunities for migrants in these locations. There is the potential for smaller towns and more rural areas which, as a result of out-migration, may have poor age dependency ratios to benefit from inward migration by those in economically active age groups.

The greater distribution of migrants with poor English language proficiency in smaller towns (often associated with employment in specific sectors e.g. agri-food) and concentration among this group is an area of policy concern. As this analysis was conducted on an area basis (rather than at the individual level) it is not possible to determine the characteristics of this group but issues such as gender, age, employment status and education level are likely to be important factors. Policy responses and tailored service provision at a local level targeting this group would be important given their higher risk of poor integration and also the potential impact on the agri-food sector from Brexit.

Reports and presentations from the ‘Migrant Integration: policy and place’ seminar are available here

Pauline White

[1] Fahey, É., Russell. H., McGinnity, F. and Grotti, R. (2019), Diverse Neighbourhoods: An Analysis of the Residential Distribution of Immigrants in Ireland, Economic and Social Research Institute and Department of Justice and Equality, funded by the Office for the Promotion of Migrant Integration