The Policy Analysis Team at the Western Development Commission (WDC) has compiled a set of Timely Economic Indicators (TEI) for the Western Region (WR) and wider Atlantic Economic Corridor (AEC).

In this Insights blog post, I provide a commentary on the latest report.

Before delving into the TEI indicators it is important to discuss the general economic outlook.

General Economic Outlook

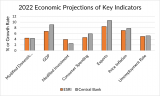

The domestic economy has rebounded strongly from the COVID-19 pandemic and the latest national economic projections, although revised downwards since last quarter, still foresee continued economic growth during 2022 (Figure 1).

Fig.1 Economic Projections for 2022.

The economic projections, strong labour market performance, and large increases in tax revenues suggest that the Irish economy and public finances are in a relatively healthy state, but several key risks remain.

The war in Ukraine has triggered a humanitarian disaster and driven food and energy prices up sharply to worsen pre-existing global supply chain problems resulting from the pandemic.

These factors are contributing to broad-based annual price inflation to heights not seen for decades. The latest CSO data shows a 9.1% annual CPI inflation rate in July. High levels of inflation reduce household purchasing power and thus consumer spending is curtailed and will pose significant challenges for rural households. CSO analysis published in June has estimated that inflation developments in the year to March 2022 are likely to have affected rural households (as well as lower-income households) to a greater extent. These households have been hit comparatively hard due to a greater share of expenditure going on energy and food. It is reasonable to assume that the 9.1% annual inflation rates recorded at the national level were even higher for rural dwellers thus targeted supports to help address the cost of living crisis should be considered.

The policy response by central banks to high levels of inflation leads to higher interest rates. Interest rate rises mean higher costs of borrowing putting downward pressure on investment and consumer spending gets hit with higher mortgage payments. Some Irish lenders have already announced mortgage rate increases. Higher interest rates also raise the cost of credit for national governments and have led to concerns over the public finances in some high-debt economies such as Italy and Greece (McQuinn et al., 2022).

High levels of inflation are a global issue and thus the global outlook for economic growth continues to be revised downwards. Provisional data in the USA suggests a technical recession (back-to-back quarterly declines in Gross Domestic Product) in the first half of 2022 and the Central Bank of England have issued warnings of the UK entering recession over the next year. Ireland is at risk from global slowdowns spilling over into domestic economic activity due to its nature as a small open economy. Slower national growth will likely translate into slower regional growth.

Another risk surrounds public service provision in response to the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine. The protection measures granted by the EU allow Ukrainian refugees access to various public services such as housing, social welfare, education and medical as well as the right to access employment. The humanitarian response is clearly essential but will come with a cost in terms of government budgetary outlay (the Irish government has set aside €3.7bn) and additional pressures on services that were already under strain such as housing. Dealing with the humanitarian crisis thus places a further emphasis on the national government to tackle pre-existing domestic policy issues.

A further risk is Brexit as continued issues surrounding the Northern Ireland Protocol persist. Trade disruptions are a particular risk for the Western Region given the comparatively high level of employment exposure in Brexit-impacted sectors (see previous Insights blog post).

Labour Market

The combined share of the Western Region and Atlantic Economic Corridor (AEC) labour force receiving state income supports or on the live register fell to 9.1% at the start of June, down from over 50% in May 2020.

Considerable regional and within region variation remains. For example, the share of the labour force in those categories combined, within the AEC counties, ranged from 7.4% in Galway to 13.2% in Donegal.

Regional and within region labour market variation have been highlighted as a key feature of the pandemic period by Lydon & McGrath (2020) & McGrath (2021). Those studies suggest that the variation is related to, and has in some cases exacerbated, historical regional structural issues within enterprise, employment, & economic activity.

As the pandemic income supports schemes have wound down, the Western Region & AEC share of the labour force on the live register has risen from 7.5% during the first half (H1) 2022 to 8.8% in July. Nationally, the figure was 8.1%. Higher regional shares of the labour force on the live register represent a continuation of a pre-pandemic trend related to regional economic & social structures.

Consumption

There were signs of a slowdown in new car registrations in the Western Region & AEC during July. This slowdown followed growth in H1. During H1 2022, new car registrations rose 2-5% in the Western Region and AEC, year on year. Nationally, there was a rise of 4% year on year.

July is a key month for car sales given the dual registration system in Ireland. July registrations were down 9-13% in the Western Region and AEC. Nationally, registrations were down 25% compared with July 2021.

There has been a slowdown in new goods registrations although 2022 levels remain at or above pre-pandemic levels in the Western & AEC. Registrations of new goods vehicles fell (17-19%) in the Western Region & AEC, year on year during H1. Nationally, registrations fell 17%.

New goods vehicle registrations for H1 were at the same level as 2019 in the AEC and 2% above 2019 levels in the WR. Nationally, registrations were down 12% compared to 2019.

Housing

The story of the housing market in 2021 was clear, housing demand held up well and continued to outpace supply thus prices have continued to rise. The sales and rental price patterns suggested the pandemic coincided with movement away from larger urban areas. The supply of available houses for sale rose during 2021 but from an extremely low base. These trends have continued into 2022.

There are encouraging signs in terms of supply growth as the regional and national planning permissions, commencements and completions data suggest continued supply growth from its low base. However, rising borrowing and material costs threaten construction delays, viability and the scale of investment in future units over the medium term. Figure 2 shows the new CSO construction materials cost index which shows the sharp increases in construction costs during 2021 and 2022.

Fig. 2 Wholesale Price Index for Construction/Building Materials

Commencements represent a good forward-looking indicator of housing supply. Figure 2 illustrates the rolling 12-month residential dwelling commencement index in the State and in the Western Region since January 2017. There has been a sharp increase, particularly in the Western Region, following a dip (driven largely by Dublin) at the start of the pandemic.

Fig. 3 Residential Units Commencnced Rolling 12-month Index 2017-22

The completions data suggest dwelling competitions could reach close to 30,000 for 2022. At this level, supply would be close to the projected national housing demand as estimated by Bergin & García Rodríguez (2020). However, Lyons (2020) estimates a much higher housing demand of closer to 50,000 per annum.

A key regional story has been the sharper rise in sales prices in more rural areas during the pandemic period and this trend has continued. Median sales prices rose in all AEC counties when comparing H1 2022 with H1 2021. Increases ranged from 9% in Limerick to 28% in Leitrim. This data is limited as it does not account for size etc. and is only indicative of price changes. The official source is the Residential Property Price Index (RPPI) which is unavailable at the county level. The RPPI for June shows an annual increase in Dublin house prices of 12% compared with 16% in the rest of the State. Border (Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Monaghan, & Sligo) & West (Galway, Mayo, Roscommon) prices rose 20%.

In addition to supply growth during H2 2022, there is likely to be mooted demand given rising interest rates and general inflation. These factors combined have led experts to expect a slowdown in house price growth throughout H2 2022 and into 2023. The Q2 2022 MyHome.ie report anticipates national RPPI price inflation to slow from double digits in H1 towards 7% in H2. The MyHome.ie Q2 report does not rule out the possibility of modest price declines. It seems more likely that any potential price falls in the shorter term would be driven from the demand side. Lyons (2022) notes that “it may not be supply that shapes the market over the rest of the year, but instead demand….interest rates are rising ‐ something that will feed into the mortgage market soon enough and which will temper demand from new buyers.”

If price falls are driven by higher interest rates that dampen demand then it is important to note that prospective buyers would need a large enough price fall to compensate for the higher mortgage re-payments they’ll face. For example, a €300,000 mortgage over a 35-year term at 3% interest means a monthly repayment of €1,148. A €235,000 mortgage, 25% lower, over the same term but at 5% interest leads to a higher monthly mortgage repayment of €1,169 (calculations as per the CCPC.ie website). Average mortgage rates in Ireland are currently around 3% (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022).

A key regional story since the onset of the pandemic has been sharper price rises in more rural areas. Lyons (2022) suggests much of the remote working regional shift in house prices is now finished and normalization is now emerging. Lyons argues that the “re-emergence of urban housing in both price and supply metrics suggests a normalization of housing, ….the shift in housing demand by those capable of remote work ‐ looks largely complete. Over the last two years, prices in places like Wexford and Roscommon have increased by one third, while prices in Dublin increased by ‘just’ 15%. This in effect means that there has been a leveling off in overall inflation since the bottoming out of prices between 2012 and 2014. Pre-covid, Dublin had seen prices rise overall by 69% from their lowest point, while prices in Cavan had increased by just 53%. Now both counties have seen cumulative increases of 95%.”

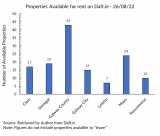

Turning to the rental market, there continues to be a chronic and worsening lack of supply in the rental market. Figure 4 shows the paucity of available rental properties in the Western Region on Daft.ie. Just 15 properties were available for the whole of Galway City. Lyons (2022) notes that the lack of rental supply is a nationwide issue, “Outside Dublin, the typical August in the late 2010s saw almost 2,100 homes available to rent at any point in time ‐ compared to just 424 on August 1st this year.”

Fig. 4 Available Rental Properties on Daft.ie in the Western Region

Under the shadow of chronic supply shortages, rents continue to increase across the country. Rents rose annually in all AEC counties during Q1 2022. Increases ranged from 4.8% in Galway city to 22.4% in Leitrim (the largest increase in the country). The national increase in rents was 9.2%.

Galway, Sligo and Kerry were the only AEC counties with lower rents increases than the national average.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of the WDC

Dr Luke McGrath

Economist

Policy Analysis Team