Introduction

Though unintended, one of the biggest experiments in employment practices is underway globally; enforced working from home. Where possible, Governments have asked that all workers conduct their normal work from home, a radical change from what has gone on before.

What will happen when some degree of ‘normality’ returns? Some commentators suggest working from home will become a much more established feature of working life. Others suggest that life and work will return to ‘normal’, only time will tell. In this blogpost I look at patterns and trends in working from home and remote working up to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The terms telework and e-Work were more common in the past but generally refer to remote working – the practice of using technology (tele-work) and electronic ways (e-Work) to work at a location separate or remote to the office. Working from home is specifically that and can be considered a subset of remote working, in contrast to working from a shared space such as a hub.

Recent History

Working from home and remote working is not a new phenomenon. As noted in the recently published Government report Remote Work in Ireland (2019), The late 90’s saw the first emergence of Government activity on remote work (then referred to as e-Work or telework). This was due to the increasing availability of ICT and broadband infrastructure. A series of actions were undertaken to promote e-Work (largely working from home).

- In 1998 the National Advisory Council on Teleworking was established by Government. Comprised of experts across a range of areas it was charged with the task of advising the Minister on telework and related employment opportunities.

- In 2000, twenty years ago, the Government approved a Code of Practice on e-Working entitled ‘e-Working in Ireland’ and the Programme for Prosperity and Fairness (2000-2002) (PPF) committed the Government to introduce e-Working options into mainstream public service employment by 2002.

- In 2001-2003, the Western Development Commission (WDC), was represented on the e-Work Action Forum, the successor to the National Advisory Council. The e-Work Action Forum assumed the role of developing tasks and strategies set out in the report, e-Working in Ireland: New Ways of Living and Working.

- The Department of Finance, in 2003 issued a circular on Pilot schemes to promote e-Working in the Civil Service. Though some individual Departments did introduce pilot schemes and may have continued the practice, no central evaluation or assessment of the policy has ever taken place.

- The Office of the Revenue Commissioners issued guidance dealing with the tax implications of e-Working for employees and employers which was updated in 2013 and updated further in April 2020 to take account of the current enforced working from home practice under Covid-19.

Environmental impacts

Generally, the earlier work on promoting e-Working focused on economic and social benefits and there was little attention paid to environmental benefits. Before the financial crisis hit, and in line with economic growth, high employment levels and greater levels of commuting, the Department of Transport published its Smarter Travel Policy A Sustainable Transport Future, A New Transport Policy for Ireland 2009-2020 (2009). This included actions to reduce travel demand and traffic congestion.

- One of the actions was to realise some of the benefits of e-Working. This included setting targets to encourage e-Working in the public sector.

- There was also an objective to research and develop e-Working centres (in effect the precursor to enterprise centres & working hubs). For example, as part of the smarter travel town initiative, a pilot e-Working centre was established in Dungarvan in 2012. This ‘Remote Working Space’, allows workers to rent space and access broadband while also operating in an office environment closer to home than the office. At that time, Westmeath County Council set up six community e-Working centres aimed at residents who travel to Dublin or elsewhere to work.

However, the financial crash ensured that e-Working as policy objective was relegated and the ensuing higher unemployment, lower employment levels and associated lower congestion levels removed some of the impetus for e-Working.

Employment Trends and Working from Home

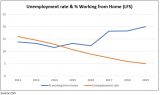

The unemployment rate and the numbers working from home rate, as measured by the Labour Force Survey (LFS) is shown in the chart below. The data from the LFS measures those who work ‘usually or sometimes’ from home.

In 2012, the unemployment rate was 16% and the working from home rate was 13.8%.

As the unemployment rate declined the percentage engaged in working from home increased. When unemployment was at its lowest, in 2019 at 5%, the percentage working from home was at its highest, 20%. One of the factors seems to be that with a tight labour market, and high employment levels, there are greater levels of working from home. More employees seek the opportunity of working from home especially given the longer journey times associated with full employment and congested transport networks. It is also argued that employers are more receptive to the practice in part related to the need to retain skilled workers.

The Labour Force Survey is a sample survey and therefore it is more difficult to get detailed regional breakdowns. The WDC uses Census data in order to get a Western Region picture.

Census data on Working from Home

The Census asks the question ‘How do you usually travel to work’? with one of the answers being ‘work mainly at or from home’. While the Census measure is valuable in providing regional data, it is limited in that it only captures those that work from home most of the working week, and excludes those who work from home one or two days per week. More recent data from the CSO (discussed below) suggest one or two days per week is the most common pattern.

Furthermore, the Census definition is inadequate in capturing the extent of e-Work as it includes all those that are self-employed and work from home (such as those engaged in agriculture and home-based sole traders such as GPs, childminders and others across all sectors) and not just e-Workers. For example, in 2011, 4.7% (83,326) of all those at work, stated they worked mainly at or from home. Of these the most significant occupational group is farmers, fishing & forestry workers, comprising over two fifths (43.5%). Excluding this group, in 2011, the share of the state’s working population reported as working ‘at or from home’ was 2.8% (47,127)[1].

[1] This compares to 3.2% (8,994) of workers in the Western Region, indicating a higher incidence of working from home in the Western Region.

The chart above depicts the numbers ‘working mainly at or from home’ (secondary right-hand axis) and the unemployment rate since the late 1990s up to and including March 2020. This excludes the Covid-19 monthly unemployment figures which was first measured in March 2020. In 1996 there was over 158,000 persons who stated they worked ‘mainly at or from home’. As noted above, a large proportion of this number is those engaged in agriculture. With the ever-declining numbers employed in agriculture it is likely that the agricultural component has continued to decline.

Most recently, there were 94,955 persons who stated they worked ‘mainly at or from home’ in 2016. This was still below the 2006 peak of 105,706, though it represents an increase of 14% between 2011 (83,326) and 2016. Once more the peak in 2006 corresponds to a period of very low unemployment, while the dip in those working from home in 2011 corresponds to a period of high unemployment. Notwithstanding the caveats with the data there does seem to be a relationship between employment, unemployment and the extent of working from home.

CSO 2018

More recently, the CSO invited submissions to the consultation on questions for Census 2021. The WDC advocated for the inclusion of a question to more effectively capture the extent of Working from home/e-Working to which the CSO agreed. The CSO conducted a pilot survey in September 2018. This found that among those at work, 18% declared they worked from home. The level of non-response among workers was low at 3%. Of those working from home, the breakdown by number of days was as follows:

Working from home 1 day per week was the most popular practice (35%), followed by 2 days a week (13%) and 5 days per week (by 11%). It should be noted that 26% of those who said they worked from home did not state the number of days. One possibility may be that their pattern changes on a weekly basis.

Profile of those working from home

- The CSO pilot results showed that the percentage of those working from home increased as age increased, peaking at 19.6% of those at work in the age group 45-49. Of this group 32% worked one day from home. The proportion of home workers decreased among workers in older age groups.

- Over half of those who worked in ‘Computer programming, consultancy and information service activities’ indicated that they worked from home. This industry comprised 3% of all workers in the pilot but 11% of all home workers were in this industry. See the CSO release here.

IBEC collects data on the extent of e-Working (largely working from home) based on a survey of their membership. The most recently published data (for 2018) shows an increasing prevalence of the practice. For example,

- In 2018, 37% of IBEC members (152 companies) had a practice of e-Working/home-working, on one or two days per week basis, up from 30% (110) in 2016.

- The likelihood of e-Working among IBEC companies increases with company size, 54% of companies with 500+ employees cite a practice of e-Working 1 or 2 days a week.

- There is a higher rate of e-Working among foreign owned companies compared to Irish, 40% and 33% respectively, and both these figures are up on two years previously – 34% and 27% respectively.

- Sectorally the highest rates of e-Working are within the Electronic services sector (69%), followed by the Financial services sector (58%).

- At a regional level IBEC members in the Dublin region have the highest incidence of e-Working, with almost half (49%) reporting having an e-Working policy of 1-2 days working from home per week. This rate drops to one-third of companies in the Cork region, one-quarter in the Mid-West and South-East and 24% in the West/North West. This regional variation supports the idea that at least some of the e-Working demand and take-up by employers is driven by the greater extent of congestion in larger urban centres.

What will be ‘The New Normal’?

So, if there is a correlation between economic growth, employment levels and the numbers working from home, what might happen once we emerge from the Covid crisis?

It is very likely that the ‘enforced’ working from home experience will have created an appetite and interest to continue the practice, by both employers and employees. The extent of this will depend on how suitable the work and role is and how effective the supports for employees working remotely has been. Some employers may find that they are pleasantly surprised with how its worked and will be receptive to continuing the practice, others may find the opposite. It is worth noting that the draft document for Government between Fiánna Fail and Fine Gael propose that public sector employees move to 20% home and remote working in 2021.

It is also likely that we will have a higher rate of unemployment than before the Covid pandemic and as with the aftermath of the financial crisis, with lower employment levels, congestion levels on public transport and road networks may drop considerably. However, the current circumstances are unprecedented and it is possible that any correlation with working from home and high unemployment will not apply while the various restrictions remain in force.

There are some differences in the context now and what prevailed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which will likely impact on ‘the new normal’.

- Technology is even more advanced with videoconferencing easily available and this can be useful for employers and employees in maintaining and promoting the remote working relationship.

- Before the pandemic, working from home has become a feature of some company’s business models, illustrating that companies can operate very successfully with all staff working remotely (e.g Shopify, Wayfair)

- The Covid pandemic forced a huge section of the workforce to engage in working from home, and in effect to trial it, albeit under rushed circumstances. While unintended, this provides a mechanism for much of the labour market to experiment working in a new way.

The most recent data[1], suggests that up to one fifth of the workforce work from home on at least a 1 day a week basis. This could be considered ‘the normal rate’ up to the occurrence of the Covid pandemic and under conditions of strong economic growth and close to full employment.

The LFS to be published in August will have additional data on the impacts of the pandemic including figures measuring the current extent of working from home.

However, as the restrictions are slowly lifted the numbers working from home will decline from their current peak and over the next few months and beyond the level of ‘the new normal’ will begin to emerge.

The levels of working from home may well be influenced by the extent to which the economy can recover relatively quickly or whether we enter a longer recessionary period. Either way ‘the new normal’ may not become clear for another year or so.

In the meantime, the WDC will continue to monitor trends and highlight issues as they emerge. As part of this work the WDC is collaborating with NUIG to gather the experiences of those working from home at this time and the findings will be discussed in a future post.

Deirdre Frost

23 April 2020

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of the WDC.

[1] CSO Pilot September 2018