In 2024, the Western Development Commission is celebrating its 25th anniversary and has published a new Report which both details the impact of the WDC in that time-period and highlights key areas of economic, social and demographic change in the Western Region generally over 25 years. It is a story of great, if uneven progress and development, of new opportunities and new challenges, of unique regional dynamics and in some cases, of persistent gaps between the national and regional picture.

In a series of blogposts released in late 2024, we describe in greater detail the changes and patterns highlighted in this Report and in doing so, illuminate a range of topics which are of relevance to life, economy and society in the Western Region [1]. In this second in the series, we explore the continuing rural nature of the region, the growth of towns, and shifting patterns over time in housing stock and housing development.

Still a (Predominately) Rural Region

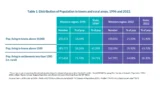

It is true that the Western Region has become somewhat more urbanised in the last 25 years [2]. In 1996, 471,458 people or 72% of the total population of 657,231 in the Western Region lived in settlements of less than 1500 people: this now stands at 64%. And in 1996, only just over 16% of the population in the region lived in towns above 10,000. In 2022, 21.5% of the population did so.

While these are notable shifts, the big story is actually how rural the settlement pattern in the Western Region remains, especially when compared to the rest of the State. Just under two thirds of people in the Western Region, or 567,991 people, live in rural areas (i.e. outside towns of 1,500+). This compares to only 33% of people in the State as a whole. Similarly, while 21.5% of the population of the Western Region live in settlements of greater than 10,000 population, the corresponding figure for the State as a whole is more than double this at 52%, and 58% in the rest of the State minus the Western Region. Despite significant changes over time, the Western Region remains largely rural in character, with the characteristics – and challenges – associated with this.

Changes in Size of Towns in Western Region, 1996-2022.

In 1996, there were only four cities/towns with a population great than 10,000: Galway, Sligo, Ennis and Letterkenny. Using the results from Census 2022, to this list we can now add two Mayo towns, Castlebar (13,132) and Ballina (10,420)[3] and Shannon in Co. Clare (10,270).

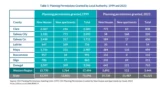

As Table 2 shows, there is significant disparity in the rate of growth of the population of these towns over the time-period between 1996 and 2022. Perhaps the most notable is the exceptional growth of Letterkenny (+88%), which stands in contrast to the relatively modest growth of Sligo (+11%). In 1996, Sligo was the second most populous city/town in the Western Region but is now in fourth place behind Galway, Ennis and Letterkenny. Galway, Ennis and Castlebar all experienced growth rates of over 50% and Galway City accounts for 9.6% of population of the entire region, a modest increase on the figure of 8.7% in 1996.

Looking more broadly at all towns in the region with a population over 1500 in 2022 (Table 3), we can observe some very interesting patterns:

- There are significantly more towns of scale in 2022:

- In 1996, there were 26 towns with a population of over 1500.

- In 2022, there were 45 towns with a population of over 1500. Table 3 contains a full list of all of these towns in order of percentage growth between 1996 and 2022.

- The towns which have experienced the most significant growth between 1996 and 2022 are generally those in commutable distance of large centres of employment.

- The towns in commutable distance of Galway are the standouts, with amongst the highest rates of growth in the Western Region. They include: Oranmore (+313%); Moycullen (+279%); Athenry (+185%); Oughterard (146%); Gort (+143); and Claregalway (116%).

- Another significant cluster of high-growth commuter towns centre on Sligo. These include Collooney (+214%); Ballisodare (+185%); and Strandhill (+159%). The growth of these towns stands in contrast to the very modest growth of Sligo Town in this period, which experienced the third lowest growth rate of any town of 1500+ in the Region between 1996 and 2022.

- A further six towns other than those already mentioned experienced growth of over 100%: Carrick-on-Shannon (+154%); Sixmilebridge (+148%); Ballinrobe (+140%); Ballyhaunis (+115%); Tubbercurry (+112%); and Claremorris (102%).

- No town in Donegal or Roscommon grew at these kind of levels though we have already noted the exceptional growth of Letterkenny relative to other towns of that scale.

- Ballyshannon is the only town of 1500+ in the region to have experienced population decline (of -19%) between 1996 and 2022 [4]. Other towns which experienced low/modest growth of under 25% include Ballina (+20%); Donegal Town (+20%); Ballinasloe (+15%); Sligo (+11%); and Kilrush (+2%).

Table 3: Towns in Western Region of 1500+ population by % population growth 1996-2022:

Housing Statistics Over 25 years

In 2002, there were 283,263 dwellings in the Western Region. By 2022, the housing stock had increased to 414,032, a 46% rise in this 20-year period. This is very close to the state average of 45%. There is no major variation in the growth figures, but Leitrim has had the highest rate of growth at 56% and Clare and Mayo the lowest (both at 39%). Clearly these are only points in time which tell us little of what happened in between. Although it is outside the remit of this blogpost to provide a detailed analysis of the vagaries of the housing market and housing development in the Western Region over the last 25 years, we can note some distinct phases and provide notable comparative statistics. These are of interest and relevance both in in the current context of a very challenging housing market and outlook and in terms of the future development and vitality of the region overall.

During the so-called Celtic Tiger era from the mid-1990s to 2008, there was a significant housing boom in the Western Region as elsewhere. This was driven by rapid economic growth, urbanisation, property speculation and tax incentives: the Upper Shannon Rural Renewal Scheme [5] was an example of the latter which had a particularly strong impact on counties Leitrim, Sligo and Roscommon. In 1999 alone, there were 10,332 new house completions, which represented 22% of the completions in the state overall. Much of the growth in the housing stock in the region in the last 25 years occurred during this time-period up to 2008.

In the period post the 2008 downturn, the legacy of this boom was an oversupply of housing in some areas – the most visible manifestations of which was the phenomenon of ghost estates – and a crash in the value of the housing in the Western Region as elsewhere. Naturally, there were much lower levels of growth in housing stock from 2011-16 in the aftermath of the housing bust and during the period of economic recession. In 2014, for example, there were only 1,071 new house completions in the whole region, just over 10% of the number built 15 years earlier in 1999. It would be 2018 before the numbers of completions in the region exceeded 2000 again and the figure for that year was only 2039 (CSO).

The numbers of new dwelling completions did gradually increase between 2016 and 2022 from the lows of the previous 5-8 years, rising to 2824 in 2020, 2753 in 2021 and 3484 in 2022 (CSO). But Western Region counties still recorded the lowest housing stock increases in the state and all seven counties recorded growth below the national average in the 2016 to 2022 period. To an extent this reflects the Celtic Tiger legacy of comparatively high levels of regional housing stock relative to population, levels of oversupply and persistently high vacancy rates. It meant that for a period of time, the Western Region had a comparatively high capacity to accommodate population growth, though with some regional variation.

However since 2016, the population has grown at a faster rate than the housing stock in all Western Region counties and this capacity has now clearly been absorbed. The last four years in particular have instead been characterised by a sharp rise in regional housing demand, a clear shortage of regional housing stock, and steep increases in house prices overall. A previous WDC Insights blogpost Housing Supply across the Western Region – Western Development Commission noted that supply did not meet projected demand in any Western Region county during 2021. The highest share in the region was recorded in Mayo (86%) and the lowest share was in Sligo (31%), which was in fact the lowest share recorded nationally. Between Census 2016 and 2022, population growth exceeded housing stock growth in all Western Region counties. Some of these counties had amongst the largest gap in the country: Leitrim increased its population by 9.5%, while the housing stock rose by just 3.4%. In Roscommon, the population increased by 8.4% per cent and the housing stock by 3.1% per cent and in Sligo, the population grew by 6.5% and the housing stock by 3.7% [6].

While prices in the region remain amongst the lowest in the country – although with some notable exceptions such as Galway City and parts of Co. Galway – the rate of increase in house prices in the region has recently outpaced the rest of the country and is also indicative of the need for increased supply. According to Daft.ie analysis, three counties in the region experienced the highest jump in house prices in the whole country from Q3 2023 to Q3 2024: Donegal, (+12.4%), Leitrim (+11.7%) and Clare (10.2%), compared to a national average of 6.2%. All other Western Region counties also experienced substantial increases: Mayo (9.5%); Sligo (9.5%) Galway (7.2%) and Roscommon (6%) [7].

To highlight this supply challenge – and in keeping with the overall theme of this blogpost – we can look at two sets of data highlighted in the 2001 State of the West Report which it is interesting to compare with current figures: the number of new house completions and the number of planning permissions granted, both per local authority/county and in the Region as a whole. For the purposes of this blogpost, we mostly compare figures from 1999 and 2023.

As can be seen from Table 4 below, the Western Region counties combined had just under a third of the number of house completions in 2023 as they did in 1999. It is noteworthy that this compares to a figure for the State as a whole of 70.29%. Some counties – Roscommon (49% of the 1999 figures) and Galway City and County (41% and 45.5% respectively) – experienced a somewhat less significant decline but four counties had fewer than 30% of the number of house completions in 2023 as they had in 1999 (Clare at 27 %; Leitrim at 25.5%; Mayo at 29 %; Donegal at 27 %).

A more sobering and important statistic from the perspective of regional balance is the decline in the national share of house completions from 1999 to 2023. Western Region counties combined had 22% of new house completions in the State in 1999. In 2023, they had only 11% of total new house completions, which is also significantly less than might be expected with a population share of 17.2% of population (Census 2022). This is broadly consistent with activity in the previous five years also (2018-2022) when the Western Region’s average share of the national house completions was 12.7%. Although to be approached with caution as only a snapshot of one year’s activity, it is also notable that some Electoral Districts (ED’s) in the region had amongst the lowest numbers of new dwelling completions in the whole country in 2023. For example, three ED’s in Leitrim (Manorhamilton, Ballinamore and Carrick-on-Shannon) had between 30 and 36 each, while Belmullet ED in Mayo and Carndonagh ED in Donegal had 38 each (CSO).

Similar but even more acute differentials can be seen in relation to numbers of planning permissions granted in 2023 when compared to the figures from 1999. As can be seen from Table 5, only 3444 planning permissions for new houses or apartments were granted in the Western Region in total in 2023, compared to 17,494 in 1999, a decline of just over 80%. In 1999, the Western Region counties accounted for 23% of planning permissions granted nationally. In contrast, in 2023, the Western Region counties accounted for only just over 8% of planning permissions granted. This is in fact slightly higher than the average for the years 2018-2022, where only 6.7% of planning permissions granted nationally were in the region. While these figures are a crude and imprecise measure of ultimate housing completion and availability – we do not have figures for how many planning permissions ultimately result in completed new homes – the (comparatively) low rates do, at the very least, suggest a weak supply pipeline and that the demand for housing will continue to significantly outstrip regional supply in the future.

When we combine the above statistics on house completions and planning permissions with the increases in prices regionally and the lack of supply, it is evident that there is clearly a need for a substantial increase in the supply of housing throughout the region. The statistics presented here suggest this is not happening at the level that is needed either to meet current demand or provide for the kind of population movement and growth which is desirable from a regional development perspective (i.e. population retention, return migration, inward migration, etc.) Without targeted interventions across multiple fronts, imbalances in terms of population growth across the regions are if anything likely to increase in the coming years with the Western Region’s share of national population decreasing further.

Footnotes

[1] For this we rely on a number of data sources. Foremost amongst these is the landmark report The State of the West published by the WDC in 2001 and which examined its recent trends and future prospects. It, alongside a range of other sources including the 1996 Census, provides us with an excellent starting point for comparisons between then and now. For contemporary statistics, we largely rely on Census 2022 but draw on other data sources where relevant throughout the series.

[2] For the purposes of this Blogpost we are using the CSO definition of living in a rural area as living outside of a town/settlement which has more than 1500 inhabitants.

[3] Both Castlebar and Ballina grew to over 10,000 population in the early 2000s – Castlebar has had a population of over 10,000 since 2002 and Ballina since 2006. Also note that there were very significant boundaries changes in Ballina between Census 2011 and 2016 as discussed in a previous WDC Insights blogpost.

[4] There were four towns with a population in excess of 1000 in 1996 which we might also expected to have moved into the 1500+ category but which in all but one case actually declined in population. They are Killybegs (-10.65%); Moville (-.03%); Kilkee (-8.8%); and Raphoe (+9%).

[5] The Upper Shannon Rural Renewal Scheme was introduced in Budget 1998 and ran until 2004. It covered all of counties Leitrim and Longford as well as 38 district electoral divisions in Co Cavan, 77 in Co Roscommon and 35 in Co Sligo. It provided lucrative tax incentives for industrial, commercial and residential development and led to significant housing development in the areas in covered.

[6] Housing Census of Population 2022 – Preliminary Results – Central Statistics Office

[7] New report reveals the most affordable place to buy in Ireland – Ireland Property Guides